Master of the Sword,

Commander of the Camel Corps,

&

Defender of Georgia

September 18, 1815 – March 15, 1883

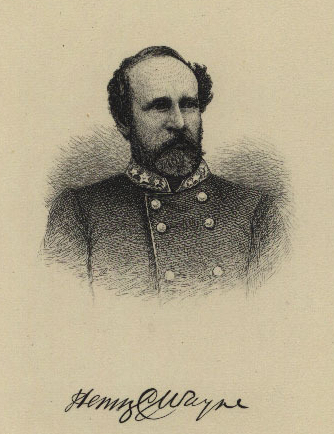

Henry Constantine Wayne, author of “The Sword Exercise Arranged for Military Instruction” was born on September 18, 1815 in Savannah, Georgia, to Mary Johnson, daughter of celebrated Virgina lawyer Alexander Campbell and wife of future US Supreme Court Justice James Moore Wayne.

Henry’s father James M. Wayne had also been born in Savannah (1790), himself the son of Richard Wayne, who had come to the American colonies from Yorkshire in England as a member of the British Army in 1760 and settled initially in South Carolina. He married Elizabeth Clifford on September 14th, 1769, and moved to Savannah in 1783 after being expelled from Charleston for being a Tory. In Charleston with the assistance of his cousin General “Mad Anthony” Wayne, himself a hero of the American revolution, Richard Wayne was able to obtain some land and make the necessary connections to do business. Despite having arrived virtually penniless, he would die one of the richest men in Savannah, having made his fortune owning plantations and business interests related to the planting, cultivating, transporting, financing, and marketing of rice, including owning and trading slaves.

Richard Wayne passed away in 1808 and left Red Knoll Plantation and nearly one hundred slaves to James M. Wayne who graduated that same year with a degree in law from Princeton University. Passing the bar in 1810, he would then serve as an officer in the Georgia Hussars during the War of 1812 (1812-15). James entered politics and was elected to the Georgia House of Representatives (1815-16), and as Mayor of Savannah (1817-19), before serving as a Judge in Georgia (1819-29) until he was elected as a Jacksonian to the United States House of Representatives (1829-35). He resigned his seat to accept President Andrew Jackson’s nomination to be an Associate Justice on the Supreme Court.

A strong Federalist, Justice Wayne famously remained loyal to the Union during the Civil War, and supported President Abraham Lincoln in a number of cases central to his efforts to preserve the union. Despite his own extensive business interests, (and vote with the majority in the 1857 Dred Scott case), prior to 1860 he had either sold, traded, or given away the vast majority of his slaves.

James M. Wayne would serve on the Supreme court for 32 years until his death from typhoid fever on July 5, 1867.

Early Military Service

After growing up in Savannah, young Henry C. Wayne was sent to receive his early education at boarding schools in Northampton, and Cambridge Massachusetts, studying at Harvard his sophomore and Junior years before attending the United States Military Academy at West Point in New York as a cadet beginning July 1st, 1834. He graduated 14th (or 15th) of 45 in his class and joined the US Army as a Second Lieutenant in the 4th Artillery.

With the young American nation engaged in concurrent conflicts with Native Americans in Florida and Georgia, as well as in Canada against the British crown (known as the “Papineau War”), eleven days later Henry Wayne was transferred to the newly expanded 1st Artillery (July 12, 1838) and sent to immediately serve on the Northern Frontier, at Plattsburg, N.Y., (1838-40) during the Canada Border Disturbances.

It wasn’t all work on the norther frontier however as Wayne wrote;

“… it was indispensable that a good understanding should be established between the British officers and our selves, as our patrols frequently traveled the road along the imaginary line with theirs, and to prevent misunderstandings growing out of accidental complications which could be easily discussed and arranged among friends, but which could not be cheerfully explained and adjusted between strangers. So, encouraged…

The next day (we held) races and amusements of various kinds and a banquet again. Plattsburgh had never seen such a carnival before. The shops took in money, as also the hotels and bar-rooms. Next morning our friends left us, …with (so) much real warmth of feeling on both sides, that was subsequently cultivated by frequent pleasant visits. One week afterward we were all indicted by the grand jury, at the instigation of some of the pious of Plattsburgh, who were horrified at our enjoyment, (and) for violating the race laws of the state of New York. We were all called, name by name, and it took all the influence of Cady, Yates, Stone, McNeal, and other leading citizens of the place to quash the indictment. So much for trying to serve one’s country.” – H.C.W.

In 1840 his regiment was moved to the boarder between Maine and New Brunswick at Houlton where he participated in the Aroostook War (sometimes called “The Pork and Beans War”), over the boundary of Maine. Fortunately the term war in this case was largely rhetorical as major combat was ultimately averted by diplomatic compromise. The regiment remained on this line, however, until just before the outbreak of the Mexican War, when four companies of the 1st went to Texas and six to Florida.

Wayne would later recall this time with the 1st Artillery:

“In seven days after leaving West Point I found myself in command, at Lewiston, N. Y., of forty-odd raw recruits, except three or four British deserters, guarding the ferry thence across the Niagara river, granting passports to persons desiring to pass from the United States into Canada, and protecting the English steamers touching or stopping at Lewiston from attack or incendiarism in revenge for the burning of the steamer Caroline below the city of Buffalo.

…In September of the same year I was relieved at Lewiston by a detachment from the 2d infantry, and ordered to proceed with my recruits to Sackett’s harbor, N.Y., and there organize them into company D, 8th regiment of infantry, that had been recently created by congress, with Col. Worth, afterward Gen. Worth, as its colonel… There was something in Worth that inspired those under his personal order with his own chivalry and gallant bearing. Reeves, too, of handsome, lithe figure, a thorough soldier and highly intellectual, was fit adjutant for such a colonel… Worth appointed Reeves adjutant of the regiment pro tem., and assigned me to the command of D company (about 900 men)… While at Sackett’s Harbor we artillery officers were employed as engineers in picketing the garrison and in other works for strengthening it.

Bidding adieu to Sackett’s Harbor, Reeves, McDowell, and I proceeded in the latter part of November, via canal, stage coach, and short sail, to Plattsburgh, N.Y., where our regiment —the 1st artillery—had just arrived from Florida, after five years’ war service there, to aid in protecting the neutrality of the northern frontier. (Wayne was assigned to company I)

…(They were) First rate soldiers for fighting and the sharp discipline of field service, their five years’ campaign in Florida, bushwhacking the Seminoles, had demoralized, however, their sense of propriety in many things, to which was added the manifest dislike and contempt of the frontier people, who sympathized with the Canadian rebels, and looked upon us as paid emissaries of the British Crown because we interfered with the aid and comfort often attempted for them. Frequent fights and collisions with the lower class of citizens and “Kanuks” refugeeing along the line kept guard duty pretty lively, and frequently every officer of the regiment was turned out to quell riots. One night, of a pay day I recollect, there was a pretty heavy breeze in town. Magruder and I were going through the streets looking up our men, when we came across one, a Frenchman, Bertrand by name. Magruder spoke to him, was glad to see him sober—he was only slightly elevated—cautioned him to keep quiet and to go down to the barracks. Bertrand repelled any idea of his getting drunk and behaving in a disorderly manner, and concluded by drawing himself up in true French grandeur, knitting his eyebrows fiercely, and slapping his right hand on his heart, exclaimed in dramatic style, “parole d’honneur, lieutenant/ Je suis Francais!” That rather took Magruder, who was given to such grandiloquence on occasions himself. “An hour passed on,” and having pretty thoroughly canvassed the town, we were returning wearily to our hotel where the officers were quartered, there being no barracks for them, when, turning into a by street, we spied a blue coat ingloriously reposing in the mud. I stirred him up with my foot, and as he turned over, grunting like a hog in a gutter, I caught sight of his upturned face. It was, alas, our magniloquent Frenchman. We consigned him to a patrol then near, and the next day “Je suis Francais ” was in the guard-house on the stool of repentance.

The regular duty beside was hard. As winter came on, and heavy snows blocked up the country roads, which were none of the best at any time, the guerrilla movements of the rebels in Canada and of their sympathizers on our side increased in number and destruction. Burnings of houses, barns, etc., were frequent, and we were constantly on the move to arrest offenders of our neutrality obligations. Serving in snow storms and in the intense cold of that region, the thermometer ranging a good part of the time from zero, below to ten, fifteen, and twenty-six degrees, came hard on our men, who had been so long under the southern temperature of Florida, and whose uniform, the same as issued in Florida, was totally inadequate to the extreme northern climate. Sentries were relieved by the hour or half-hour, instead of every two hours as usual, and patrol duty was fearfully severe. We had many bad cases of frost-biting, and two or three deaths from freezing on post, not withstanding the constant visits of the officers, sergeants, and corporals of the guard.

…In the spring of 1840, Gen. Scott, the great peace-maker, was hurried from Washington to Maine, and our regiment being the nearest at hand, was ordered forthwith to support him. …(Although) nothing of importance happened. The survey of the north-eastern boundary was provided for, and begun; Maine was quieted, the rest of the states breathed freely again.

…I remained at Houlton until December, 1841, when I was ordered, unexpectedly to me, to proceed to West Point and report for duty as assistant instructor of artillery, vice McDowell, appointed adjutant of the academy. This severed my immediate connection with the regiment, renewed only occasionally until we came together in Mexico.”

– H.C.W. in a letter dated February 17, 1875

On December 12th, 1841, Henry Wayne returned to the United States Military Academy at West Point to serve as an assistant instructor of Artillery, and Cavalry, and later Master of the Sword Exercise, and Instructor of Infantry tactics. On May 16th, 1842, he was promoted to First Lieutenant (1st Artillery), and on July 1st, 1843 he began to serve as Quartermaster (July 1st, 1843, to June 11th, 1846).

Master of the Sword

Unfortunately no known surviving records tell us the full extent of Henry Wayne’s own training with the sword beyond the instruction he would have received during his own time as a cadet at West Point, but it is very likely that his first instructor was his father, himself a veteran swordsmen from his time serving as a Cavalry officer with the Georgia Hussars, additionally it is probable that he would have had some exposure to fencing with foils during the course of his New England boarding school education.

In 1843 Henry C. Wayne became the first member of the US military to serve as Master of the Sword of the United States Military Academy at West Point, holding that position until 1846. Prior to Wayne all previous Masters of the Sword at that institution had been civilian instructors, N. Albert Jumel, a civilian, had held the post from 1832–1837, instructing then cadet Wayne during his own time at the Academy before passing the position on to Ferdinand Dupare (1837–1840), and then to H.G. Boulet who served until Wayne took over.

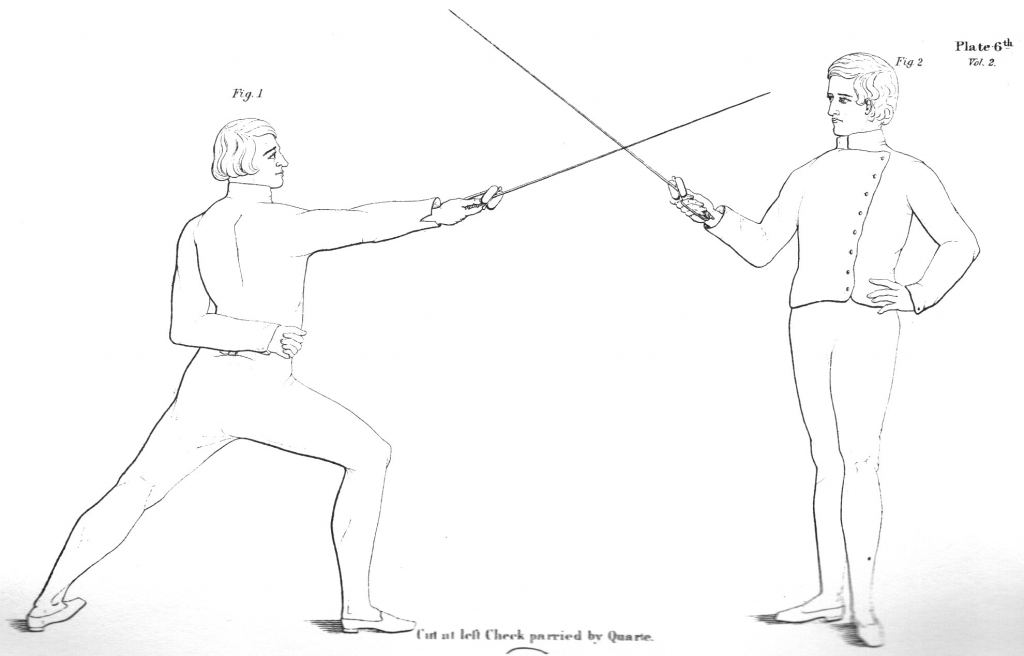

While serving as Master of the Sword, under the suggestion of the Superintendent of the Academy, Major R. Delafield, US. Engineer Corps, Henry Wayne first began compiling his swordsmanship treaties. Developed with the idea of imparting the greatest amount of theoretical and practical instruction on the use of the sword as possible in the limited time available to cadets, Wayne’s system left his students with a knowledge of principals which they could use to perfect their art by continued practice. Combining his own words and experience, with those of the greatest swordsmen of his day, Wayne’s treaties presents a system of swordsmanship based on solid principals, which he would test, train, and refine for three and a half years before arranging the material into a concise program of instruction for quickly training the officers of the American Military. Unfortunately publication of the treaties would be delayed when Wayne went to join the 1st Artillery fighting the war with Mexico in 1846.

War with Mexico

In Mexico, Henry C. Wayne who had been promoted to Staff Captain on May 11th, 1846, served as an assistant to the Quartermaster General, where he was predominantly responsible for seeing to the transportation of supplies to the front, although he would see action participating in the decisive victory of the outnumbered American forces at the Battles of Contreras, and Churubusco.

The 1st Artillery received the commendation of its brigade and division commanders for each and every action in which it was present during the war, and its losses—21 percent of its whole strength killed or wounded—attest its military zeal and fidelity to duty. The battle of Churubusco was especially fatal, there the loss in officers and men was 45 out of a total of less than 300. For his part, Henry C. Wayne was brevetted a Major on August 20, 1847 for “Gallant and Meritorious Conduct in Battle”.

After the war Wayne was stationed at the Quartermaster-General’s Office in Washington, DC, where he was placed in charge of the Clothing Bureau (1848-55), and on February 22nd, 1851 Wayne vacated his line commission with the 1st Artillery and was promoted to Captain in the Quartermasters department.

In Washington DC Wayne moved to a “pleasant old-fashioned residence on G Street, between Seventeenth and Eighteenth Streets, which in subsequent years became the Weather Bureau… across the street was the French Legation.” where he was neighbors with Jefferson Davis, and the author Marian Campbell Gouverneur. There he was finally able to finish his treaties “The Sword Exercise Arranged for Military Instruction” after the project was resumed at the request of fellow officers who had seen Wayne’s method in action and were convinced of it’s usefulness. The book was published in 1850 in Washington DC as the first official manual of sword instruction for the United States Army.

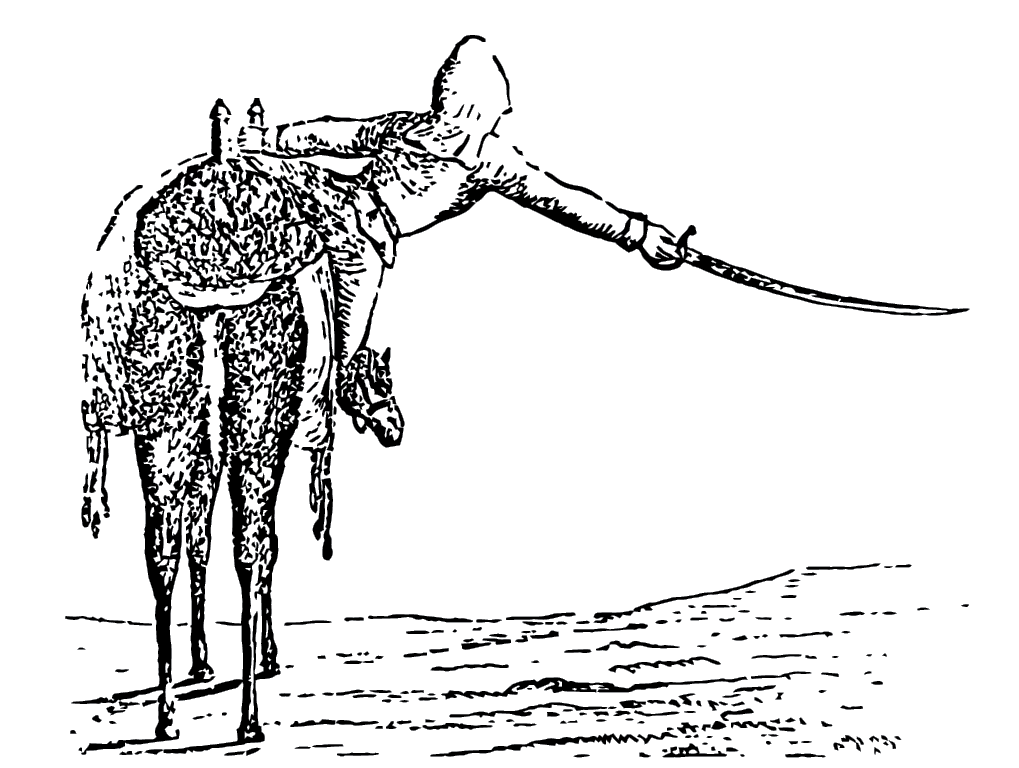

“One advantage of the camel over the horse was the ability of the rider to make a more extensive saber cut by holding the frontpiece of the saddle and leaning to the side.”

-Letter of W. Re Kyan Bey, Secretary to the Viceroy of Egypt to Edwin Deleon, US. Consul General in Egypt on the Treatment and Use of the Dromedary, US Congress, Senate Miscellaneous Document Number 271, 35th Congress. First Session, Washington. D. C., 1857-58

The Camel Corps

During the war with Mexico, Wayne had befriended Major George H. Crossman, US Army, also a graduate of West Point. Crossman had served as Zachary Taylor’s quartermaster in the Seminole war in Florida, where the difficulty of transporting supplies caused him to suggest in 1836 that camels be introduced and used for that purpose. He made a study of the subject, and twenty years later was considered an authority on the subject, encouraging the War Department to use camels for transportation of people and supplies in the newly conquered American Southwest.

North America had been home to the earliest prehistoric camels, which had stood less than a foot tall. Evolution had wiped out those prehistoric North American ancestors, but their descendants, double-humped Siberian and Chinese bactrian, and speedy, single-humped North African Arabians called dromedaries became essential to transport and commerce in those regions where they lived. Spanish and English colonists in America had previously experimented with importing camels, including into Virginia as early as 1701. These early experiments had failed, but the era of westward expansion renewed interest.

‘‘Major Wayne, chief hero of the camel experiment, is probably the only man that ever drove a pair of dromedaries to harness in the United States, outside of a circus. He did this in 1856, while bringing his charges up to Texas from the seaboard, and found the team satisfactory.’’ – Charles F. Lummis

Wayne’s own experience in the southwest during the war with Mexico convinced him of the usefulness of Crossmen’s idea, and in 1848 or earlier, Wayne conducted a more detailed study and recommended the importation of camels to then Senator Jefferson Davis of Mississippi and the War Department. Davis then asked Wayne to make a case to Congress for camel transport. In his formal report, in addition to using camels for transport, Wayne also included a martial option: a fleet Arabians might be used against the Indians in “promptly punishing their aggressions.” Congress balked and when Senator Davis introduced the measure in Congress in 1851 and again in 1852 it was literally laughed out of committee.

Newspaper editors, lecturers, and authors continued to garner interest the idea, as Davis continued to urge Congress to pass a bill to experiment with the camels, but was unsuccessful until appointed Secretary of War in 1853 by President Franklin Pierce. In his annual report as Secretary of War for 1854, Davis wrote, “I again invite attention to the advantages to be anticipated from the use of camels and dromedaries for military and other purposes….”

As a part of the effort, that same year Wayne translated THE ZEMBOUREKS, OR THE DROMEDARY FIELD ARTILLERY of THE PERSIAN ARMY from the original French.

THE ZEMBOUREKS, OR THE DROMEDARY FIELD ARTILLERY of THE PERSIAN ARMY.

Finally on March 3, 1855, the US House of Representatives appropriated $30,000 for the “purchase and importation of camels and dromedaries for military purposes.”

Henry C. Wayne was assigned Commander of the new “Camel Military Corps,” and tasked to procure the camels. On June 4th, 1855, Henry C. Wayne departed for New York City to view the USS Supply, under the command of then Lieutenant David Dixon Porter (later Admiral Porter in the Civil War) which had been assigned to aid in his mission.

Wayne first sailed to London on the 19th of May aboard the Hermann to examine camels in the London zoo, next traveling to Paris on the evening of June 20th 1855 to learn of the use of the camel in North Africa by the French, before he journeyed to Italy to rendezvous with the USS Supply. There they went to Pisa to view the 250 camels that were said to be able to do the work of 1000 horses on the estate of Grand Duke Leopold II of Tuscany, where camels had been used in labor for 200 years.

Once they had arrived in the Mediterranean Sea, Wayne and Porter began procuring camels, after a brief stop in Naples, the Supply arrived at the port of Goletta in Tunis (modern day Tunisia) where Wayne had the honer of being the first official visitor from the United States, he was presented before the new sultan who gifted two camels to the people of the United States.

Recalling his experience, Wayne would write in a letter dated August 10, 1855:

“I was presented to Mohammed Pasha. On presentation, I requested the consul-general to say to the Bey “that I was glad of the occasion that brought me into the waters of Tunis, as it gave me an opportunity, as an officer of the government of the United States, to pay my respects to him, and to congratulate him, in the name of the President of the United States, upon his accession to the throne; to assure him of the friendly disposition of the President and the people of the United States towards the regency of Tunis, and to express the desire that the amicable relations hitherto existing between his country and my own might, under his wise reign, be continued and extended.” To which the Bey replied, “that he thanked me for my visit, and received with sincere pleasure the congratulations of the President; that he wished well to the President and people of the United States, and he hoped that nothing would occur to disturb the harmony at present existing between the two governments, which it was his desire to continue and cherish.” – H.C.W.

Additional stops were made in, Malta, Greece, Turkey, and Egypt where they initially had difficulty securing permits to export their camels until a suitable bribe of two American rifles had been paid.

“Yesterday, at Mr. De Leon’s request, I gave him two Minie rifles, as he said he had promised them to the viceroy on the 30thultimo. To make the gift complete, I added a bullet-mould and a swedge.” – H.C.W.

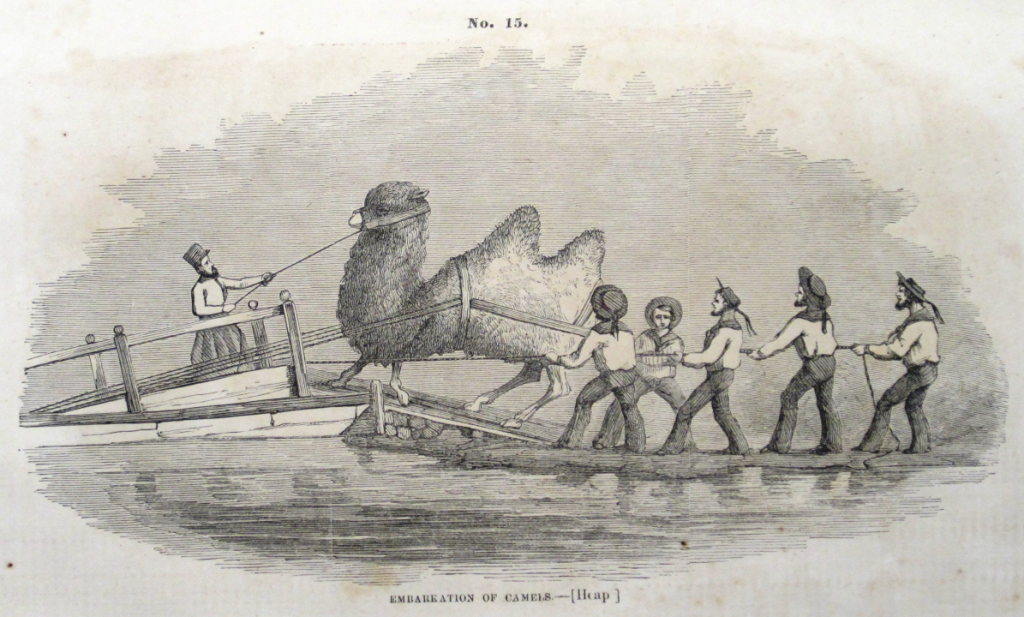

In total 33 animals were acquired (19 females and 14 males), including two bactrian, 29 dromedary, one dromedary calf, and one booghdee (a cross between a male bactrian and a female dromedary). Additionally they purchased pack saddles and covers, being certain that proper saddles could not be purchased in the United States. Wayne and Porter also hired five camel drivers, some Arab and some Turkish, and on February 15, 1856, with there initial mission successfully completed, the USS Supply set sail for Texas.

A report written by Wayne aboard the USS Supply on it’s almost three month return journey at sea, dated April 10th, 1856 gives us a vivid picture of the difficulties encountered traveling the world in the 19th century:

“Your instructions were, to visit Egypt, Syria, Asia Minor, Persia ifpossible, to examine the zembourek or camel artillery in use there; Salonica, that had been mentioned to you as a suitable place for procuring and shipping camels, and such other countries in the east as might be deemed advisable for the purposes of the mission. These instructions have been executed as far as time and opportunity permitted, and the particulars reported to you in previous communications…

In relation to our visiting Persia, the inquiries we have made lead us to the conclusion that, though we might readily get there, our return, owing to the blocking up of the roads by snow, would be impossible until next spring… Syria was not visited on account of the cholera and fever prevailing throughout it during the summer, and from the risk of shipping during the winter months in its ports, which are only open roadsteads, affording no protection to vessels at anchor. … You further directed me to visit the Canary islands, on my return, for the purpose of examining the camels used in them, and where they have been in use, according to Humboldt and others, ever since the conquest of those islands by the Spaniard—about four hundred years ago. Unfortunately, this order I was unable to execute, as, after several days of fruitless effort to reach those islands, on account of variable and head winds and a gale, the attempt was abandoned and the ship stood on her course to America.” – H.C.W.

(Drawing by G. Wynn Heap, artist with the first expedition to acquire camels from the Middle East. From Reports Upon the Purchase, Importation and Use of Camels and Dromedaries, 1855-’56-’57.)

After a brief stop in Jamaica where the presence of the camels caused a great deal of excitement, the USS Supply arrived in Indianola, Texas on the afternoon of April 29th at 4:30pm after a rough Atlantic crossing with one more camel that it had departed with, proving the ease with which the camel could be transported at sea, far easier than horses or mules in Wayne’s opinion. When the group arrived back, they experimented with the animals in the deserts of the western United States, and established strict rules for the care, watering, and feeding of the animals, no experiments were conducted regarding how long a camel could survive without water.

“Its milk is good to drink, and is not distinguishable from that of cows. I have used it in my tea every morning for some weeks, knowing it to be camel’s milk, without perceiving any difference in color or taste.” – H.C.W.

On Davis’ orders, Porter set sail again for Egypt to purchase more camels. While Porter was on his second voyage, Wayne acclimated the camels from the first voyage for three weeks before setting out for the interior, marching toward Camp Verde, Texas, by way of San Antonio. Outside Victoria, Wayne met 10 year old Pauline Shirkey, he gave her mother, Mary, clippings of camel hair from which she spun thread and knit a pair socks, a gift Wayne sent to the President, the attached letter read:

“I have the honor to enclose herewith a pair of socks knit for the President by Mrs. Mary A. Shirkey, of Victoria, Texas, lately of Virginia, from the pile of one of our camels.”

Whether the President actually wore his camel’s-hair socks is lost to history. Prior to the caravan departing for San Antonio, Pauline was given a memorable ride. “The camel bells were jingling…and I was sitting on the back of this unusual steed,” she recalled 75 years later.

Wayne made plans to establish a ranch and breeding program for the camels, but his plans were denied when he was instructed:

“The establishment of a breeding farm did not enter into the plans of the department. The object at present is to ascertain whether the animal is adapted to the military service, and can be economically and usefully employed therein.” – TH. S. JESUP, Quartermaster General.

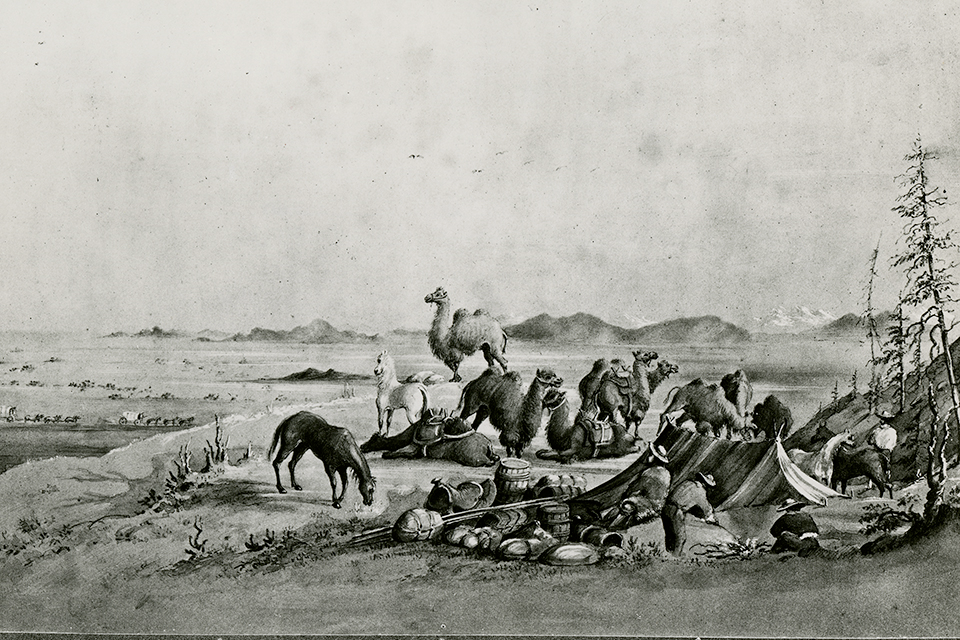

On 26-27 August, Wayne moved the herd the final sixty miles northwest from San Antonio to Camp Verde, a more suitable location for the US Army’s caravansary. There he constructed a camel corral (khan) exactly like those found in Egypt and Turkey. By the time the camel herd settled at Camp Verde, the animals had demonstrated the advantages they offered the army, once away from populated areas, Wayne advised Davis that, camels delivered high-capacity, low-consumption, long-range desert transport for freight, mail, even infantry.

“…viewed in relation to this vast unsettled country, where the roughness of the roads limits materially the loads placed in the wagons, and where the general want of water through out regulates the day’s journey of mules, six camels will accomplish as much as two six- mule teams, and in less time, and at much less expense.” – H.C.W.

On February 10, 1857, USS Supply returned with a herd of 41 more camels. During the second expedition, Porter hired “nine men and a boy,” including Hiogo Alli. While Porter was on his second mission, five camels from the first herd had died. The newly acquired animals joined the first herd at Camp Verde, which had been officially designated as the camel station. The Army now had seventy camels.

To satisfy Secretary Davis’ concerns about the usefulness of the camels to the military, Wayne devised a practial field test. He sent three wagons, each with a six-mule team, and six camels to San Antonio for a supply of oats. The mule drawn wagons, each carrying 1,800 pounds of oats, took nearly five days to make the return trip to camp. The six camels carried 3,648 pounds of oats and made the trip in two days, clearly demonstrating both their carrying ability and their speed. Several additional tests also served to confirm the transporting abilities of the camels and their superiority over horses and mules.

“The burden animals can be used for transporting supplies from San Antonio to the camp and to other points. The dromedaries may be sent express anywhere along the frontier or within the settlements, as necessity may require, and may be used as pack animals to scouting parties instead of mules. In some cases men may be mounted with a small gun throwing shrapnel…. These experiments may be so conducted as not only to show the absolute value of the animal for burden and for the saddle, but also a relative usefulness in comparison with the horse, the mule, and waggoning.” -H.C.W.

Davis was much pleased with the results and stated in his annual report for 1857, “These tests fully realize the anticipation entertained of their usefulness in the transportation of military supplies…. Thus far the result is as favorable as the most sanguine could have hoped.”

Through Wayne’s thorough testing program it was soon apparent that the camel was simply not suited to the American style of combat. The configuration of the camel’s nose, while well evolved to filter out blowing sands, impeded breathing during violent exertion, and the camel’s lung capacity was such that it could not maintain a sustained rapid pace or violent action. When overly excited, the animal would blow the buccal membrane which normally hangs in the pharynx, balloon fashion, from its mouth, further limiting its air supply, another serious disadvantage in combat was the fact that the camel, unlike the horse, was unwieldy in close situations. Ultimately however, the biggest drawback to the combat usage of the camel was the resistance of both men and officers to the animal. Compared to the horse, the camels required significantly more care, otherwise they could develop a severe form of highly contagious mange, which was difficult to cure. Additionally, the camel, at best, smelled different from the horse, at worse, it stank. Even after the troopers had adjusted to the smell, the camels had three habits to which the men would not reconcile themselves. First, although camels were typically docile, they could be stubborn, and, when annoyed with their keeper, or disciplined for their stubbornness, they would often vomit their cuds on the disciplinarian, or deliver a vicious bite. This and the camels’ ability to defecate without any warning whatsoever onto anyone standing behind the animal quickly overrode whatever enjoyable or useful qualities they may have possessed. Finally, the troops, almost universally, complained of motion sickness after riding the animals for any distance or at a gallop, and in the end, after a series of incidents, a rash of complaints and a series of tests, Wayne unhappily reported that the combat usage of the camel in America was not feasible.

If the camel was a failure for the American Army as a combat animal, it was ideal for the quartermaster units in charge of transporting supplies. Ordinary dromedaries could easily carry a 550-pound load, slightly more than twice what a common pack mule was expected to carry. The larger dromedaries could comfortably pack 700 to 800 pounds and, on occasion, would carry as much as 1000 pounds for short distances. The larger and stronger bactrians could carry close to three-quarters of a ton with ease.

In February 1857, Wayne staged a demonstration for the doubting public. He wrote of the incident:

“Needing hay at the camel yard, I directed one of the men to take a camel to the quartermaster’s forage-house and bring up four bales. Desirous of seeing what effect it would produce on the public mind, I mingled in the crowd that gathered around the camel as it came to town. When made to kneel down to receive its load and two bales, weighing in all 613 pounds, were packed on, I heard doubts expressed around me as to the animal’s ability to rise under them; when (two more bales were put on, making the gross weight of the load 1,236 pounds, incredulity as to his ability to rise, much less to carry it, found vent in positive assertion … to convey to you the surprise and sudden change of sentiment when the camel, at the signal, rose and walked off with his four bales of hay, would be impossible.” – H.C.W.

Wayne was also able to successfully test the idea of using camels in support of cavalry units:

“Lieutenant Chablis went out with a small party, and with him I sent a dromedary to transport the provisions and forage [corn] for the men and horses, seven each. The next day he returned and from his report, and that of his men, the trial was very successful, the dromedary following the horses wherever they went, not only keeping up with them, but showing that if not restrained, he would have gone ahead of them. The weight transported was between 300 and 400 pounds.” – H.C.W.

By October 1856, Major Wayne expressed the belief that he had conclusively proved the camels’ worth for both military and civilian cargo transportation in the Southwest. He wrote:

“The usefulness of the camel in the interior of the country is no longer a question here in Texas among those who have seen them at work, or examined them with attention.” -H.C.W.

In 1857, James Buchanan was elected President of the United States, John B. Floyd succeeded Davis as Secretary of War, and at Wayne’s recommendation he too was to replaced by Captain Innis N. Palmer. With his task apparently coming to an end, Wayne was transferred from the project by February 1857 back to the Quartermaster General’s office in Washington DC.

“The prejudices of regimental officers against the exercise of command over them by an officer of the staff precludes me from the control of enlisted men. I have no desire to hold a questionable position. In making this proposition I sacrifice personal wishes to what I conceive to be a necessary duty. At all times, however, I shall be ready to contribute to the experiment whatever of knowledge and of systematic employment I possess and have digested.” – H.C.W.

Prior to leaving Camp Verde, Wayne recommended a large-scale field trial of the camels in order to prove the value of the humped creatures once and for all in the minds of the American people and Congress. Officials from the War Department liked the idea, and 25 camels (both dromedaries and bactrians) were included with the military survey expedition tasked with mapping a wagon road from Fort Defiance, Arizona, to the Colorado River. President Buchanan personally appointed former Navy lieutenant turned explorer, Edward Fitzgerald Beale, to lead the survey. On the 25th of June 1857, the expedition, complete with 46 mules, 250 sheep (for delivery to Fort Defiance) and 25 camels, surged westward from Camp Verde.

Beale reached Fort Defiance on the 21st of February 1858, ending the Camel Corps’ first and only major expedition. The camels’ complete success as cargo transports convinced the new Secretary of War, John B. Floyd, of their value, and, after receipt of Beale’s report, he proclaimed, “The entire adaptation of the camels to military operations on the plains may now be taken as demonstrated.” Floyd requested an government appropriation in 1858 for the purchase of 1000 camels, the request was ignored. He tried again in 1859, unfortunately by that time Congress was deeply preoccupied with the ever widening tensions between North and South, and the request was ignored again. When the Civil War broke out in 1861, the Federal camel herd was split between two widely separated posts, 80 animals at Camp Verde, Texas, and 31 at Fort Tejon, California.

The results of the camel tests were ignored by both sides, the Union considered the animals a liability, the Confederacy, however, assumed the bulk of the burden from their Northern brothers when they captured Camp Verde on the 28th of February 1861. The remaining 31 Union camels at Fort Tejon remained at that post, used only for modest hauling purposes and for mail transportation nearby the fort. In the end, the remaining camels were either sold, many to circuses and mining companies, or released into the wild where they would occasionally be seen. “Old Topsy,” the last documented descendant of the original Camel Military Corps, died in 1934.

Henry Wayne received the First Class Gold Medal of Mammal Division by the Société impériale zoologique d’acclimatation of France in 1858 for his role in the introduction of the camel into the United States.

Civil War Service

As Georgia yielded to the powerful forces of secession, it became clear that the bitterly divided nation would soon be at war. James and Henry Wayne, father and son, expressed different ideas of duty and honor and choose different paths after Georgia seceded from the Union, and although his father, then a sitting Justice on the US. Supreme court, famously remained loyal to the Union, Henry C. Wayne resigned his commission with the US Army on December 31st, 1860 and joined the confederacy to protect his home in Georgia.

The reasons for the division of the Wayne family are complex and although Henry Wayne expressed that he did not fundamentally believe in a states right to secession, his sense of honer compelled him, and with his fathers blessing Henry C. Wayne was in rebellion against his nation, while remaining loyal to his father and protecting his family’s assets, and defending his state and his home.

Wayne was heralded as the “first Georgian to respond to the call of his state.” and he accepted Governor Joseph E. Brown’s offer to be Adjutant and Inspector General of the Georgia militia. He wrote “(to have hesitated) would have been to be recreant to my family, to the land of my birth, to my name and to my pledge to some of my friends…”

December 16th, 1861, Henry C. Wayne was commissioned a Brigadier General in the Confederate Army.

January 7th, 1862 Wayne resigns his Confederate commission four days after being ordered to Mananas, Virginia, instead choosing to remain in Georgia to resume his position as Adjutant and Inspector-General of Georgia rather than leave for military service elsewhere during the war.

As Adjutant and Inspector-General, he was responsible reorganizing the Georgia militia for defense of the state, subdividing it into companies, regiments, and two brigades, before tendering their services to General Joseph E. Johnston. Additionally he commanded Georgia’s Quartermaster General, Ira Roe Foster, to immediately provide supplies for the troops, instructing Foster to “proceed personally, or by duly accredited agents, into all parts of the state, and buy 25,000 suits of clothes and 25,000 pairs of shoes for the destitute Ga. troops in the Confederate service.”

Governor Brown praised Wayne’s efforts to the Georgia state legislature in 1862 saying, “No one has labored more incessantly or zealously.”

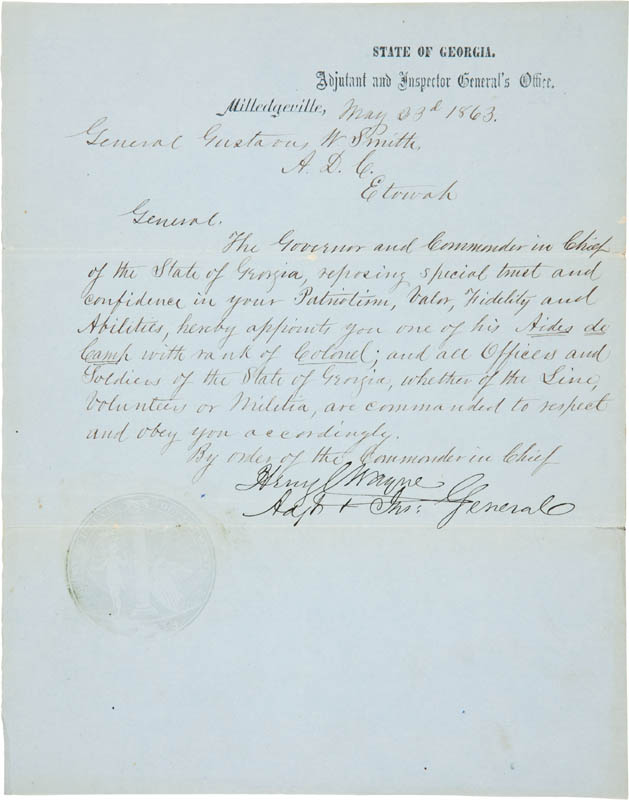

Milledgeville [Georgia], May 23, 1863

General Gustavus W. Smith, A. D. C., Etowah.

“The Governor and Commander in Chief of the State of Georgia, reposing special trust and confidence in your Patriotism, Valor, Fidelity and Abilities, hereby appoints you one of his Aides de Camp with rank of Colonel; and all Officers and Soldiers of the State of Georgia, whether of the Line, Volunteers or Militia, are commanded to respect and obey you accordingly”

Henry C. Wayne

Adj. & Ins. General.

Prior to beginning his service at home in Georgia Wayne paid a final visit to his parents in Washington DC, saying what must have been a difficult farewell, borrowing enough money for his return trip to Georgia and agreeing to look after the family property and business interests. Not only was the Wayne family concerned about the confiscation of property, but also about the destruction and damage inflicted by enraged secessionists seeking revenge against Justice James Wayne and his family’s considerable holdings in the state.

In April 1861, the Confederate government issued orders to confiscate all assets of known Unionists, Union sympathizers, and even family members of northerners. Confiscated assets were quickly sold, and the proceeds used for the Confederate war effort. James Wayne’s assets were targeted immediately once it became clear that he was not returning to Georgia, and his properties were confiscated.

In Savannah during the summer of 1861, the former family home on the corner of Oglethorpe Avenue and Bull Street in Savannah, though occupied by the family of William Washington Gordon, a railroad entrepreneur, was repeatedly vandalized and decorated with a harsh concoction of human excrement, animal waste and other wretched refuse that was thrown on the doors, windows and front porches of the homes of known Unionists, sympathizers, and relatives of Unionists.

Henry Wayne honored his word to his father and fought hard to protect his family’s assets. As James Wayne predicted, the Confederate government confiscated Wayne property in Savannah and throughout Georgia and prepared to liquidate his assets. As promised, Henry Wayne stepped in with a barrage of letters first writing to Governor Joseph E. Brown of Georgia, next he implored Alexander Stephens, Vice President of the Confederacy and friend of the Wayne family, and asked Stephens to step in on behalf of him and his father and prevent the confiscation of Wayne property, all to no effect. Finally, Wayne wrote directly to President Jefferson Davis, with whom he still had a cordial relationship. His efforts were finally successful, and annoyed by Wayne’s relentless requests, his fathers property was released to Henry Wayne by order of President Jefferson Davis who told his Secretary of State, Judah P. Benjamin, to “find the letter of Wayne to end his stupid vaporizing.” Henry Wayne subsequently held his father’s assets secure throughout the remainder of the war.

The Battle of Balls Ferry, GA

Henry Wayne did briefly see action during the Savannah Campaign as Sherman’s 60,000 man army was marching across Georgia “to the sea” destroying everything in their wake. Wayne was called upon to command a small force composed of the Corps of Cadets from Georgia Military Institute, Pruden’s Battery of Light Artillery, Talbott’s company of Cavalry, Williams’s Militia company, the Factory and Penitentiary Guards and the Roberts’s Guards (composed of conscripted convicts), totaling about five hundred men against the 15th and 17th Corps of General Sherman’s Union army.

Wayne’s experience has been preserved for us in his own words within the official report to the Governor:

Reports of the operations of the Militia, from October 13, 1864 to February 11, 1865,

by Maj. Generals G. W. Smith and Wayne, together

with memoranda by Gen. Smith, for the improvement of the State

military organization.

Georgia. Macon, Boughton, Nesbit, Barnes and Moore, State Printers [1865]

Pages 16-23

STATE OF GEORGIA,

Adjutant and Inspector General’s Office,

Milledgeville, February 6th, 1865

To His Excellency

JOSEPH E. BROWN,

Governor of Georgia :

Your Excellency : An accidental injury to my right hand has prevented a report earlier, of the operations of the Militia under my command since the evacuation of Milledgeville by the State Forces on the 19th November, 1864.

Parting with your Excellency on the evening of the 19th of November at Gordon, where I had been ordered by you at the request of General Cobb, C. S. P. A., dispositions for the night were made as well as could could be done. The command consisted of the Corps of Cadets, Prudens’ Battery of Artillery, Talbotts’ Company of Cavalry, Williams’ Company of Militia, the Factory and Penitentiary Guards, and the Roberts Guards, (convicts.) In all, nominally, 500 men, with 460, aggregate, actually fit for effective service, and all under the immediate direction of Major F. W. Capers, Superintendent of the Georgia Military Institute, whom I had appointed Executive Officer.

On Sunday morning, the 20th, my telegraphic communication with Macon was cut at Griswoldville by the enemy, about 10:30 AM. At 12 PM, I learned that the enemy, in force, were moving on my right towards Milledgeville. Further information of the enemy’s movement on Milledgeville reached me in the afternoon. At 8 PM., having received no communication from Macon since the cutting of the wires in the morning, and feeling in consequence that I was thrown upon my own responsibility, I determined, on consultation with my principal officers, to abandon Gordon, as its occupation was of no value, either for the protection of property (all trains and stores having been sent off), or as a military position, and to full back to the Oconee Bridge, as the most important point on the Central Railroad to be defended. Telegraphing for a train from below, to move down to this new position, one was sent up on Monday, at about 12:30 PM. The guns and baggage were immediately put on, and at 4 PM., as the men were getting on, a report of the enemy in heavy force three miles oft’, was brought in. Talbot’s Cavalry was sent forward to hold them in check, while the train moved off’, and did so handsomely, covering it also from a flank movement on our right to cut us off, and the retreat of the Artillery horses sent down with their drivers by the Irwinton Turnpike. A few scattering shots as the train moved off, dropping harmlessly around it, announced the entrance of the advanced guard of the enemy’s 15th Corps into Gordon. We brought off everything safely, and arrived at the Oconee Bridge at 6:30 o’clock, PM.

At the bridge, I found a guard of 186 men, consisting of Heyward’s Company of South Carolina Cavalry, a section of Artillery (two pieces) under Lieutenant Huger, and a Company of the 27th Battalion Georgia Reserves, under Major Hartridge, C. S. F. A., sent up two days before by General McLaws, from Savannah.

Tuesday, the 22nd, was spent in examining the ground and in preparations. The orders from my superiors were to hold the bridge to the last extremity. The movement of the enemy was not a little raid, but his army marching on Savannah. The bridge could be flanked on the right from Milledgeville, Buffalo Creek only intervening, and on the left by Hall’s Ferry, eight miles below, as well as attacked in front. The long and thick swamps on our side of the river prevented the use of Artillery or Cavalry at either the bridge or Ball’s Ferry. An Infantry defence only could be made, and rough field works, to be hastily thrown up, as there were no previous preparations for cover. Major Hartridge, on his arrival, had judiciously burned the main bridge over the Buffalo and guarded the crossing, and placed a light picket at Ball’s Ferry, but his force was too small to prevent any formidable resistance. Three other bridges over the Buffalo were destroyed, the crossings guarded, and the picket at the Ferry strengthened, reinforcements were called for from Savannah, but General McLaws had none to send, and the small command, of not quite seven hundred men, had twenty miles, at least, of line to watch and guard. Held to extreme orders, with an overwhelming force in front and on both flanks, these gallant officers and men cheerfully prepared to do their duty and meet their fate.

Wednesday, the 2nd the enemy (a Brigade of Kilpatrick’s Division of Mounted Infantry, as we were informed by prisoners taken) appeared on our front at the bridge, about 10:45 AM, and commenced the attack, which was handsomely met on the west bank of the river by the Cadets, under Captain Austin, and by a detachment of the 4th Ky. Mounted Infantry, under Colonel Thompson, sent to my assistance that morning by General Wheeler, and by one gun of Pruden’s Battery, mounted on a platform car, under the gallant Pruden himself. Retiring slowly as they were pressed back to the bridge by the superior force of the enemy, the detachment of the 4th Kentucky was withdraw, the Factory and Penitentiary Guards and Williams’ Militia sent in, and a line formed on the east bank of the river, under the direction of Major Capers, who had been assigned to special command at the bridge. At 12:30 PM, it was reported to me from the ferry, that the enemy, in numbers, were on the opposite side, had driven in our pickets, seized the flat which the officer in charge there had not destroyed on the approach of the enemy, as he had been ordered to do, and were crossing the river. Major Hartridge was immediately sent down with Heyward’s Company of South Carolina Cavalry, Talbot’s Cavalry, the Company of the 27th Battalion, the Roberts’ Guards and Huger’s section of Artillery, to meet this force and drive it back over the river, reclaim the flat, and establish a strong guard at the ferry. This duty the Major performed in a most gallant manner, marching ten miles, driving back over the river between two and three Hundred of the enemy who had crossed —carrying out my orders completely. Leaving Talbot’s Cavalry and the Roberts’ Guard as an additional guard, and picketing Blackshear’s Ferry, still four miles lower down, ho rejoined me with the remainder of his troops at the bridge, at 10:30 P. M, The force Major Hartridge encountered was subsequently reported to be the advance of the 15th Corps.

As the attack at Ball’s Ferry, if successful, necessitated the abandonment of the bridge, by placing the enemy in our rear, the forces at the bridge being as it were in a pocket, I had directed the baggage to be packed, the telegraph to be disconnected, and prepared for an orderly retreat, should we be compelled to abandon the ground. Taking post at the head of the trestle, I awaited the result of Hartridge’s movements. His success re-established our position. In the meantime, the enemy at the bridge had been hammering Capers and his command in a lively manner, but without making any impression. Night closed active operations, but only to excite our men to sleepless vigilance, lest, under the shelter of darkness, the enemy might, with his larger numbers, seize an advantage.

Thursday the 24th opened bright and cold, and with daylight recommenced the attempt on the bridge. At Balls Ferry the enemy had fallen back to his main body. Talbot crossed with some of his cavalry and gathered forty-three rifled carbines, and a quantity of clothing, knapsacks and other articles apparently abandoned in a hurry. Prisoners and scouts reported the enemy in three columns, about sixty thousand strong, moving in our front, and on our right and left. At 1:30 PM the enemy opened at the bridge with light, long range of artillery, but after throwing a few shells withdrew it. Enemy reported building a raft in the woods below Capt. Warthen with fifty-three men, Washington Militia, some mounted and some on foot, reported for duty. At 5 PM enemy reappeared in small numbers, a reconnoitering party at Balls’ Ferry, and after delivering a few shots retired. Bridge hard pressed all day—small parties of cavalry marauding on the other side of the Buffalo, and occasionally feeling the crossings. At 8:15 PM, the enemy under cover of night, and of heavy vollies of small arms, succeeding in forcing a tiring party up to the far end of the trestle on their side, almost without range of our best rifles, and fired it. Colonel Gaines, with five hundred men joined me at midnight by direction off General Wheeler, who had crossed in the morning at Blackshear’s Ferry, and at Dubin.

Friday the 4th, at 1AM, General Hardee arrived with a portion of his staff. At daybreak, the enemy opened heavily at the Ferry on Talbot, with two pieces of artillery and small arms. Trestle work burning slowly towards the bridge, enemy covering its progress. At 9 AM, General Hardee returned to No. 13. Enemy reported moving in large force on Sandersville and No. 13. At 11 AM, Lieutenant Colonel Young, 30th Georgia, sent to the Ferry with a portion of Gaine’s command to reinforce Talbot, who was hard pressed, but well covered and confident. The 4th Kentucky detachment patrolling the roads to our right. During the afternoon the fire having approached the bridge, the enemy withdrew from our front, moving to our left. In the evening, Major Capers assuring himself that the enemy had entirely left our front, extinguished the flames which had reached the bridge, but only charred a few feet of it. The attempt to destroy the bridge by a direct attack in front had failed. At 9:15 PM, Colonel Young commanding at Balls’ Ferry, reported that the enemy were preparing to cross above and below him, that his men and ammunition were nearly exhausted, and if held in his position until daylight, his command would be sacrificed. On telegraphing this report to General Hardee, at No. 13, for which point the enemy were also making, I received orders to withdraw all my forces, and fall back on No. 13.

Saturday, 26th, 5 minutes past 1 AM, the forces were withdrawn, bringing off everything, and at 5:30 AM reached No.13. Here Huger’s Artillery was turned over to General Wheeler, who was impeding the enemy’s march from Sandersville. At 9 AM, left for the Ogeechee bridge, No. 10, which I had been ordered by General Hardee to occupy. Arrived at 1 PM. at the Ogeechee.

Sunday 27th —Enemy cut the Waynesboro Railroad at Waynesboro in the morning. Ordered to fall back to Millen and fortify. Cavalry left in the front by order of General Hardee, to watch the bridges. Arrived at Millen 3:30 PM, with the infantry and Pruden’s Battery, in all 423 strong fortified around the Railroad Depot.

Monday 28th — 2 AM, received information from General Wheeler that Kiilpatrick with his command of between 4,000 and 5,00 men had left Waynesboro for Millen. My scouts on that road gave us no notice of the enemy. At 8:15 AM, Major Black, Inspector General to General Hardee, arrived from the road with the same information. As Kilpatrick, was on good authority, reported “to have left Waynesboro for Millen, and as my scouts on the direct road between the two places give me no hint of his approach, I concluded that his march was to cut me off at No. 5 below, and that the safety of my command required me to fall back to or near that point, Major Black concurring, the command was moved back to No. 4 behind the little Ogeechee Bridge, arriving there at 3:30 PM.

Thursday 29th —Occupied in preparing defences. Sent Major Hartridge with his company, of the 27th Battalion, to Savannah, as ordered by General Hardee, Rumors vague as to the movements and force of the enemy above. Command reduced to the Cadets and Milledgeville Battalion of Infantry, Prudeus’ Battery, and the Washington County Militia, in all 350 men. — Emanuel Militia, mounted, numbering about thirty men. reported for duty under Captain Clifton.

Wednesday November 30— Sent Major Capers, with an engine up the road for information ; communicated with General Wheeler.

Thursday, December 1—Moved with the command up the road to No. 6, as a corps of observation. Leaving the command there, proceeded on the engine with some of my staff to No. 7. Enemy reported in force at No. 8, and crossing to west bank of the -Oconee. Can learn nothing positively of the force on the right.

Friday, December 2—Captains Bridwell and Darling, Quartermaster and Commissary, C. S. P. A., who had volunteered their services at Gordon, returned to their station at Milledgeville, the enemy having left that place. Ascertained positively that the enemy, said to be the 17th corps, are moving down the road; and that another column, reported to be the 15th corps, are three miles below me on the other side of the Oconee. A courier from General Wheeler reports a heavy cavalry force moving down on my right from Waynesboro’. Fell back again to No. 4 ½, arriving there at 4 PM.

Saturday, December 3—Daybreak joined by the State Line and 1st Brigade Georgia militia, of General Smith’s Division, from Savannah, under direction of Colonel Robert Toombs, Inspector. General 1st Division, 10 ½ AM Learned that the 15th corps, on the other side of the Ogeechee, was moving for No. 2, as I had supposed. As this march, if not anticipated, would cut my rear, determined on consultation with Colonel Toombs, to fall back to that point, our only dependence being upon the railroad, having no wagons nor other means of transportation and no cavalry to cover our movements. Three columns of the enemy being also in our front on the railroad and on our right. At 11 AM, joined by General Baker, C. S. P. A., with his Brigade of North Carolinian’s. Explaining to him the position of the enemy, he agreed with me that No. 2 was our post, and the command was accordingly moved down to that station. On arriving at No. 2, I was met by Major Black, of General Hardee’s staff, with instructions to return to No. 4 ½, and that further reinforcements would be sent to me. Obeyed the instructions, though in opposition to my own judgment and of my officers, and reoccupied No. 4 ½ about 7 P. M.

Sunday, December 4—Reinforced early in the morning by Anderson’s and Phillips’ Brigades, Georgia militia, of General Smith’s Division. Formed line of battle behind the little Ogeechee, throwing back the right to protect that flank, as the river was fordable above us, with open pine barren to the Savannah river, enabling a superior force to envelop ns easily. Our force consisted of about 4000 men and three pieces, of Pruden’s battery. No cavalry. Assigning General Baker as executive officer in command of the line, and Major Capers as Chief of the Staff, waited for events. At 1:35 PM, the advance of the 17th corps appeared on our left in front of the cadets, one of whom — Coleman, a vidette —brought down the officer of the party, who demanded his surrender. Skirmishing began on our left and in front of the bridge on the railroad. At 4 PM General McLaws arrived from Savannah with orders from General Hardee to assume the command. At 5 ½ PM General McLaws having learned the position, directed me to withdraw the troops quietly during the night and fall back to 1 ½ At 7 PM, enemy ceased skirmishing and began entrenching in our front.

Monday, Dec. 5, 2 AM —Troops withdrawn, and in march for 1 ½ Central Railroad. Arrived at 1 ½ , and while examining for a line, received orders to fall back still farther and take up a position within three and a half miles of the city of Savannah.

Tuesday, Dec. 6—Arrived at the lines, within three and a half miles of Savannah, at 2 AM. At 10 AM examined the line to be occupied by the State Troops. It extended from the Central Railroad to the Savannah river. Batteries were erected at the Central Railroad, at the Augusta Road’ and at Williamson’s plantations on the river, but no lines for infantry, nearly three quarters of a mile, had been thrown up.

Wednesday, Dec. 7—Gen. Smith returned to duty, having been temporarily unwell and turning over to him his own Division and Major Capers’ Battalion, I reported to General Hardee for any assistance I could render him.

Remaining in Savannah until Monday, the 19th of December, when General Hardee informed me he had orders to evacuate the city, I left with my Staff in the evening, and riding up on the South Carolina side, reached this place again Tuesday, the 27th December, and resumed my office duties as Adjutant and Inspector General of the State.

In concluding this report, I take the opportunity of bringing to the notice of your Excellency, and of officially expressing my thanks to Majors Hartridge and Capers, and to the officers of my Staff improvised for the occasion, …for their valuable counsel, confidence and active assistance at all times and under any circumstances

My thanks are also due to the gallant officers and men whom I had the honor to command, and to whom I am indebted for support. I would conspicuously mention Majors Hartridge and Capers, and Captains Talbot, Pruden, Austen and Warthen. The gallantry of these gentlemen cannot be surpassed. …They have been brilliantly illustrated by the Corps of Cadets, whose gallantry, discipline and skill equal anything I have seen in any military service. I cannot speak too Highly of these youths, who go into a fight as cheerfully as they would enter a ballroom, and with the silence and steadiness of veterans….

The Roberts’ guards (convicts) generally behaved well, their Captain, Huberts, is a brave and daring man. Enclosed is a list of those of the Company, who, sharing the fortunes of our troops, have returned to this place and been furloughed for thirty days. I recommend them for the full pardon conditionally promised.

With deep gratitude to a kind Providence, it is my pleasure to report that my losses were small. But 5 killed and 5 wounded. One of the wounded. Cadet Marsh, has since died, as also Mr. Stephen Manigault, of Charleston, S. C, of Heyward’s Cavalry, who received his death wound under Hartridge, at Ball’s Ferry, on the evening of the 23rd of November. Advanced in years, possessed of wealth, and of high social position, all of which might have screened him from military service, he nevertheless did not hesitate to uphold, as a private in the ranks, the political opinions he maintained. He fell gallantly fighting for them. His friends have already embalmed his memory, but it may be permitted to his accidental commander, personally a stranger to him, but who had learned his worth, to add a leaf to the chaplet of laurels that crowns his tomb, and to hold up his conduct as an example for imitation.

What injury was inflicted upon the enemy we could not learn. Prisoners taken reported their loss at 45 on the first day, 23rd November. Three bodies unburied were found at the Ferry on the 24th, and I have learned since my return that a number of graves opposite the Ferry mark in part the stubbornness of Talbot’s resistance. Very respectfully,

Your ob’t serv’t,

HENRY C. WAYNE, Major General

Post Civil War

Though Savannah fell in December 1864, Sherman’s subsequent occupation uncharacteristically left most of the city intact, including the Wayne property. Having held most of his father’s assets secure throughout the war, the Wayne family were able to recover from the South’s economic collapse quicker than most, yet with limited personal prospects, Wayne express that, “(I have been) ruined by the war, both at the North and at the South.”

After the war Wayne took a strong interest in public affairs, he was strongly pro-union and deeply federalist, becoming an outspoken republican who often contributed articles to newspapers. Wayne might have described himself at this time as a conservative, constitutional, liberal republican gentleman who despised carpetbaggers, writing; “They are simple holders of office for there own pockets and in the influence of New England aspirants. I know this of my own knowledge.”

His writing occasionally expressed an optimism for the nations future; “that matter (slavery) is for us, set at rest and I see now no cloud to darken the future of the Nation for many years to come.” even though he knew that the path going forward for the country would not be easy. “The negophobia must, as all other manias, run its career, and the white race won’t lose in the long run. But there will be some blood spilled before the end shall be reached.”

He strongly supported US President Ulysses S. Grants plan for the (voluntary) annexation of Santo Domingo (the Dominican Republic) to the United States, it was hoped that that American control of the island would help compel Brazil, Puerto Rico, and Cuba to abolish slavery, and that if African Americans had the option of moving to the island where they would be a political majority, violent groups in the South, like the Ku Klux Klan, would have to end violence against African Americans or lose their source of cheap labor. Both Grant and Wayne were careful to avoid directly advocating African American emigration to the island. A commission, sent in 1871 to make an objective assessment as to whether annexation would be beneficial to both the United States and the Dominican Republic, included civil rights activist Frederick Douglass and reported favorably on the plan.

Henry Wayne wrote in a letter to his friend Secretary of State Alexander Fish on May 13th, 1874 in support of the plan, writing that Santo Domingo should be granted full statehood, and speaking out against those who; “sought to restrain the intelligence of the future educated negro in the Southern States, as an element of political discord by which Radicalism might hope to maintain it’s unconstitutional control on public affairs. I did what I could to correct the error, and thought I found many intelligent men agreeing with me, we could not override the excess of partisanship.”…

…“It is not to be doubted that as the colored people become educated they will aspire to social & political elevation corresponding to their intellectual capacity. And that the dominant white race will regard these aspirations and resent them. The acquisition of St. Domingo will, in my opinion, relieve both races from this internecine dilemma and secure to both peace, friendship, and the full enjoyment of all civil and political rights secured by the Constitution;… Moving thus, each race in its own sphere, without heartburning collisions, they will come to pari passu to a properappreciation for each other.”. – H.C.W.

On July 5, 1867 Henry Wayne inherited his fathers assets, most of which were obtained before the Civil War, including substantial stock ownership of three Georgia-based railroads, two plantations in Georgia, thousands of acres of pine land, several lots in the city of Savannah, rental property, cash, and thousands of dollars worth of personal property. Once he had converted most of his father’s inheritance to cash, he operated lumber mills and related businesses between 1866-1875 felling trees on Wayne property throughout Georgia, unfortunately this prosperity would be short lived.

His wife, Mary Nicoll Wayne (born 1821) passed away on April 26th, 1873, they had had four children together; two daughters, Mrs. Mary Wayne Patterson and another whose name is unknown, and two sons, one who’s name is currently also unknown and is presumed to have died young, while the other, Capt. Rev. Henry N. Wayne followed in his fathers footsteps, serving in the US Army and naming his own son Henry (Henry T. Wayne).

Sometime between between October 15th, 1874 and January 2nd, 1875 he became aware that a “systematic course of fraud on the part of my partner has swept away pretty much all of my capital.” Henry Wayne was ruined financially.

President Grant appointed Wayne as US Consul to Japan at Kanazawa on the 5th of November, 1873 but he was forced to declined the offer to his great personal regret, as the pay was relatively low and his financial situation required him to stay at home and look after his daughters, even postponing the marriage of the youngest.

In August 1874 with his financial situation worsening, out of concern for the welfare of his daughters, Wayne wrote to President Grant looking for work in Government service, Grant reportedly responded “If there is anything that can be done for Wayne I should like to do it.”

By the end of that year Henry Wayne had joined the Catholic Church, and remarried, this time to Ms. Adelaide Hartridge, additionally he was also finally able to see his daughter(s) married, although his financial situation had become even more desperate, and on May 28, 1875 he wrote again to his friend Secretary of State Hamilton Fish:

“The result of my unfortunate business partnership nearly ruined to me, and the defalcation (misappropriation of funds) of [omitted] in New York, my agent, and trustee of my children, has entirely finished me, leaving me without income, other than what I might be able to earn. These are hard blows at my time of life, but the Good Father has left me health, good spirits, energy, and a capacity for hard and continued labor, so that if I can find something to do I can win my way yet. Here at the South there are no literary, art or industrial employments, and as I know nothing practically of the cultivation of cotton or rice the agricultural field is closed to me, even had died the means to enter it, which I have not now. Politically, being a Republican, there is no local opportunity for me.“

He appears to eventually have found gainful employment serving his country as a US Commissioner, and the 1880 census records this as his occupation.

Henry Constantine Wayne died on March 15, 1883 (aged 67) and was buried in Laurel Grove Cemetery, Savannah, Georgia near his father. His will left everything he owned, consisting only of personal property (except for a portrait of his mother which was left to his son Henry), to his second wife Mrs. Adelaide Heartridge Wayne, with whom he had no children.

Bibliography

- Cullum, George W. (George Washington), 1809-1892. Biographical Register of the Officers And Graduates of the U.S. Military Academy At West Point, N.Y.: From Its Establishment, In 1802, to 1890, With the Early History of the United States Military Academy. 3rd ed., rev. and extended. Boston: Houghton, Mifflin, 1891.

- Georgia. Adjutant-General’s Office, Henry C. (Henry Constantine) Wayne, and Gustavus Woodson Smith. Reports of the Operations of the Militia, From October 13, 1864 to February 11, 1865. Macon: Boughton, Nesbit, Barnes and Moore, State Printers, 1865.

- McMahon, Joel C., “Our Good and Faithful Servant”: James Moore Wayne and Georgia Unionism.” Dissertation, Georgia State University, 2010. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_diss/15/

- Letter of W. Re Kyan Bey, Secretary to the Viceroy of Egypt to Edwin Deleon, US. Consul General in Egypt on the Treatment and Use of the Dromedary, US Congress, Senate Miscellaneous Document Number 271, 35th Congress. First Session, Washington. D. C., 1857-58. p 33.

- Lawrence, Alexander A. “SOME LETTERS FROM HENRY C. WAYNE TO HAMILTON FISH.” The Georgia Historical Quarterly, vol. 43, no. 4, 1959, pp. 391–409. JSTOR, www.jstor.org/stable/40577962.

- Shapard, John “The United States Army Camel Corps 1856-66” Military Review, vol. LV, no. 8, August 1975, pp.77-89. https://www.armyupress.army.mil/Journals/Military-Review/Directors-Select-Articles/The-United-States-Army-Camel-Corps-1856-66/

- Scott, Winfield Major-General, to William L. Marcy, Secretary of War, Dispatch communicating Scott’s official report of the Battles of Contreras and Churubusco August 28, 1847. A Documentary History of the Mexican War, DMWV, 1995

- United States. War Dept, Henry C. (Henry Constantine) Wayne, F Colombari, and Jefferson Davis. Report of the Secretary of War: Communicating, In Compliance With a Resolution of the Senate of February 2, 1857, Information Respecting the Purchase of Camels for the Purposes of Military Transportation. Washington: A. O. P. Nicholson, printer, 1857.

- Reports Upon the Purchase. Importation and Use of Camels and Dromedaries. 1855-’56-’57, US Congress. Senate Executive Document Number 62, Committee on Military Affairs, 34th Congress, Third Session, Washington. D. C., 1857

- Wayne, Henry C. (Henry Constantine), 1815-1883. “The Sword Exercise: Arranged for Military Instruction”. Washington: Gideon and Co., 1850.